I am struck by the visual representation of Sherlock in this episode, the extent to which the narrative of his clash with Moriarty, the “Great Game” of the heading, is reinforced by Sherlock’s physicality and framing, the focus on his figure as it moves through the steps of the “game”. If this is a dance, Sherlock is not leading it, and his place in it is curiously feminised as an object of desire as well as a slightly hapless follower to Moriarty’s lead.

In visual terms the episode is particularly full of white, stark, empty settings – the snow of the Belarus prison room which opens it, the empty spaces of the Thames-side crime scene and the art gallery.

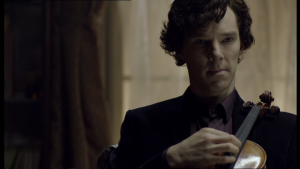

Sherlock inhabits these as a dark, isolated centrepiece, gaining focus from the contrasts which also lend him resonance as alienated and alien, apart and slightly inhuman (look at his disengaged body language, leaning back, in the left-hand shot above), associated with the cold of the snowscape or the Thames-side body site, or the gallery’s white marble. Sherlock himself is interestingly shot in this episode, high-contrast shots which emphasise his paleness and render him inhumanly beautiful, marble rather than flesh.

He is framed as an object of desire – Moriarty’s desire, John’s desire, but also through our identification with the camera, ours. That first frame, above left, is notable for its reinforcement of the feminisation enacted on him by Moriarty’s dominance of the episode – the lighting and camera angle emphasises the actor’s bone structure, but also make him look younger and rather vulnerable.

This positioning of Sherlock as the object of desire is played up by the episode’s narrative, which presents the “Great Game” as a tussle for Sherlock’s attention. Moriarty’s introduction in the persona of the slightly camp “Jim” makes this desire explicit in leaving his phone number, but it’s also inherent in Moriarty’s flirtatious language later in the episode: “hello, sexy”; “a little getting-to-know you present”; “is that just a Browning in your pocket, or are you pleased to see me?” John’s jealous reaction reinforces this – “I hope you’ll be very happy together”.

The framing points up the series’s continual play with the tension between emotion and intellect, between engagement and detachment – Sherlock must be seduced because he is detached, but he also hold within him the potential for passionate involvement, a response to the seduction. He shares with Moriarty the potential for both extremes, cold and suppressed in one moment, excited and manic when thrilled by intellectual stimulation. And, of course, the other extreme to Belarus’s snow is the melodrama so characteristic of the series – in this episode the Golem, the planetarium struggle to Holst’s “Planets” with the wildly interrupted lighting – which externalises and dramatises the emotional extreme. Melodrama, after all, is about an excess of emotion. The series is almost forced to include it simply to balance out the detective’s intellectual detachment.